I traveled to places that do not exist. I met people without a future, living in the past. I visited many places in western Ukraine, in Volhynia. Today, there are only empty space of the former Polish villages and towns. Almost all they disappeared in the year 1943.

They can be found on old maps. In early spring, when snow melts it can be seen, where there were houses. Material is only emptiness and the echo of the past.

I'm looking for what does not exist, and I'm trying to tell the story about Volhynia, the land contaminated by death.

Only an echo remains. Everything else has gone.

Villages, schools, churches. And the people. Sixty, seventy, maybe as many as a hundred thousand.

No one remembers Wołyń, either in Lwów or in Kiev. For them, it lies somewhere out west. For us in Warsaw or Krakow, it’s somewhere in the east. For us and for them it’s another world. As if nobody’s.

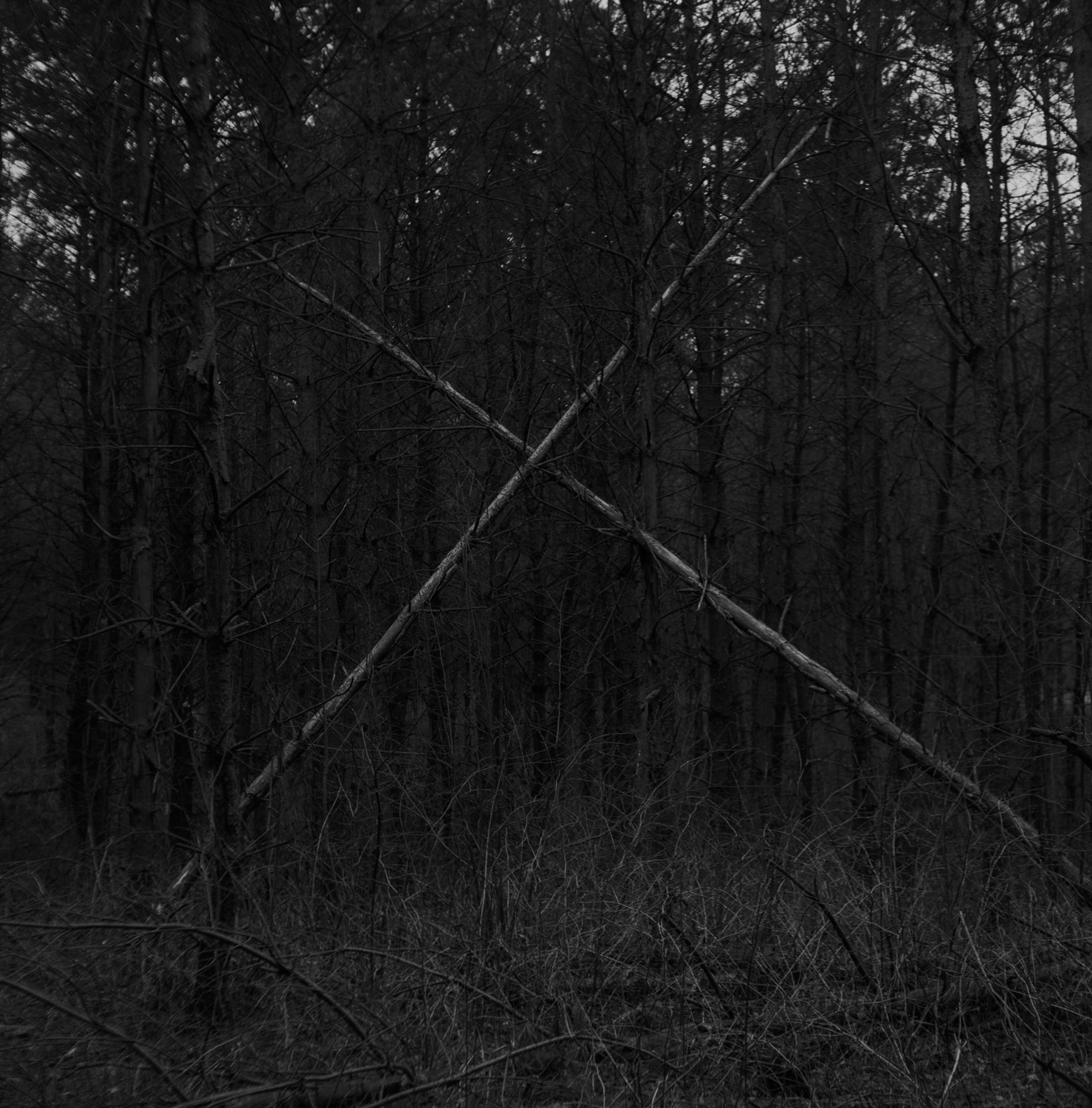

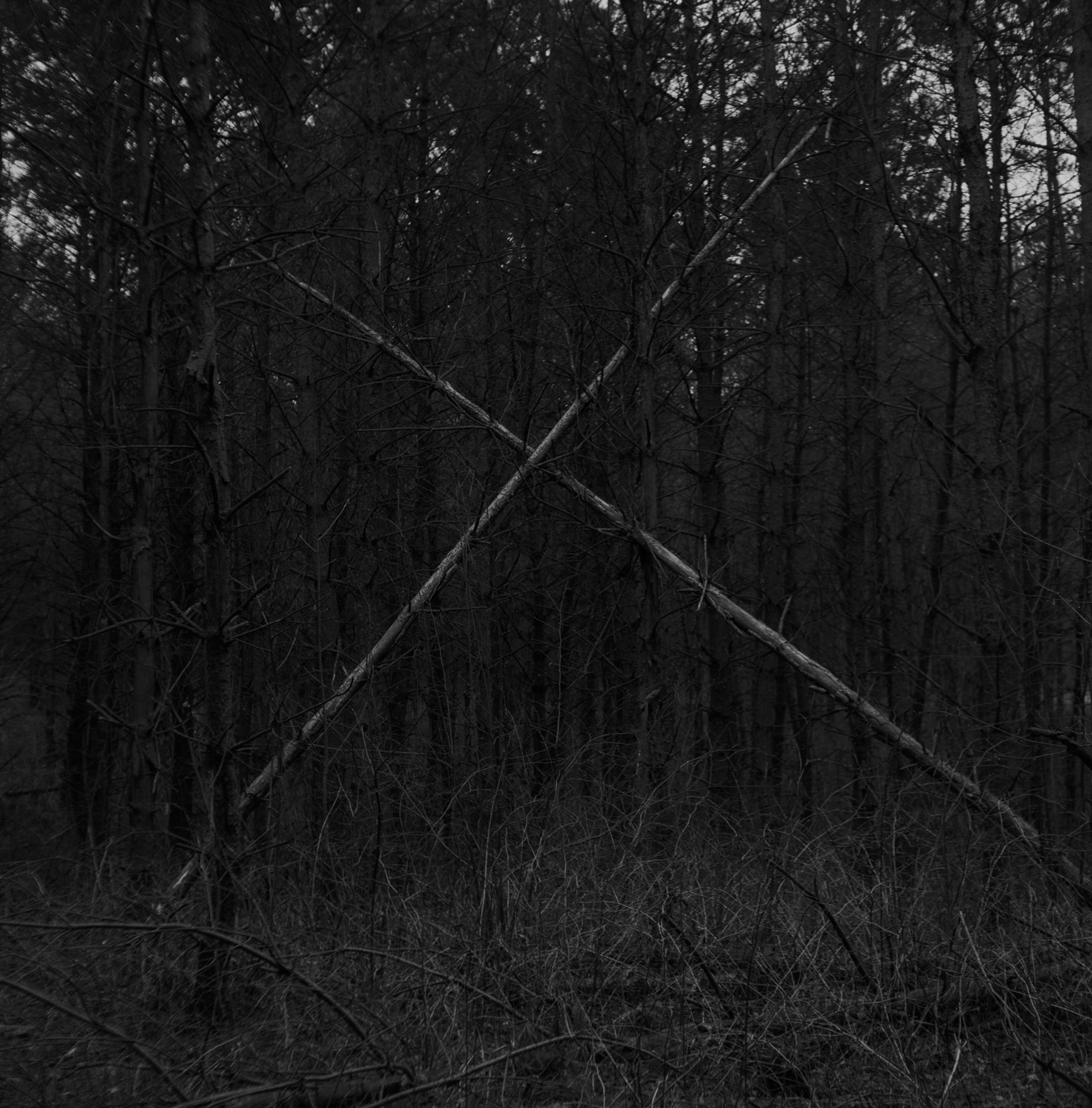

There is nowhere to escape to, nowhere to hide, the forest is distant and the road far.

Or one could run uphill and then downhill through the rolling countryside, ...

...and pray.

They killed with knives, pitchforks, hatchets and they shot.

But they impaled the children of the basalt mine-workers.

Only the former neighbours knew.

They remembered a terrible stench that lasted several days. The odour made them dig a deep pit.

It’s difficult to find this mass grave now.

In early spring, the last snows melt along the outlines of bygone houses. White squares. House stood by house.

On Sunday, like every week, the town filled with visitors arriving for mass

the Brzeziński family from Woronczyn, the Kraszewski family from Zapust, the Kulesza family from Żurawiec, Bronka Słotwińska from Twerdyn, the Gardzyński family from Warszawka, the Skibiński and the Zienkiewicz families from Rudnia, and Teofil Sidorowicz from Trystak. The two young Jonaszko daughters came as well, as did the 17 year old Julka Filipkówna from Kisielin itself and several dozen others too. All told, there were over a hundred.

She seized the child and started running away across a field. A bullet wounded her head. She fell.

She got up again and ran on. The son survived. He became Poland’s first cosmonaut.

The barn burned rapidly.

Bones were uncovered for years after.

There’s an elder there – the house has gone,

another elder – another house,

elder groves – a whole village.

There’s just a wood now.

Then, hesitatingly, she says that no, she's Zośka.

That she came from a Polish family, that her husband was Ukrainian, that her mother was in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. She says she remembers everything. She remembers that field.

Further down there, Wola Ostrowiecka had a school. A wooden cross stood there. After it had decayed, a metal one was driven in. Then, larger crosses were erected, over there and here in Ostrówki, on concrete pedestals with spaces for stone tablets for inscriptions about what had happened here in 1943. They’re still missing.

I traveled to places that do not exist. I met people without a future, living in the past. I visited many places in western Ukraine, in Volhynia. Today, there are only empty space of the former Polish villages and towns. Almost all they disappeared in the year 1943.

They can be found on old maps. In early spring, when snow melts it can be seen, where there were houses. Material is only emptiness and the echo of the past.

I'm looking for what does not exist, and I'm trying to tell the story about Volhynia, the land contaminated by death.

Only an echo remains. Everything else has gone.

Villages, schools, churches. And the people. Sixty, seventy, maybe as many as a hundred thousand.

No one remembers Wołyń, either in Lwów or in Kiev. For them, it lies somewhere out west. For us in Warsaw or Krakow, it’s somewhere in the east. For us and for them it’s another world. As if nobody’s.

There is nowhere to escape to, nowhere to hide, the forest is distant and the road far.

Or one could run uphill and then downhill through the rolling countryside, ...

...and pray.

They killed with knives, pitchforks, hatchets and they shot.

But they impaled the children of the basalt mine-workers.

Only the former neighbours knew.

They remembered a terrible stench that lasted several days. The odour made them dig a deep pit.

It’s difficult to find this mass grave now.

In early spring, the last snows melt along the outlines of bygone houses. White squares. House stood by house.

On Sunday, like every week, the town filled with visitors arriving for mass

the Brzeziński family from Woronczyn, the Kraszewski family from Zapust, the Kulesza family from Żurawiec, Bronka Słotwińska from Twerdyn, the Gardzyński family from Warszawka, the Skibiński and the Zienkiewicz families from Rudnia, and Teofil Sidorowicz from Trystak. The two young Jonaszko daughters came as well, as did the 17 year old Julka Filipkówna from Kisielin itself and several dozen others too. All told, there were over a hundred.

She seized the child and started running away across a field. A bullet wounded her head. She fell.

She got up again and ran on. The son survived. He became Poland’s first cosmonaut.

The barn burned rapidly.

Bones were uncovered for years after.

There’s an elder there – the house has gone,

another elder – another house,

elder groves – a whole village.

There’s just a wood now.

Then, hesitatingly, she says that no, she's Zośka.

That she came from a Polish family, that her husband was Ukrainian, that her mother was in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army. She says she remembers everything. She remembers that field.

Further down there, Wola Ostrowiecka had a school. A wooden cross stood there. After it had decayed, a metal one was driven in. Then, larger crosses were erected, over there and here in Ostrówki, on concrete pedestals with spaces for stone tablets for inscriptions about what had happened here in 1943. They’re still missing.